Pierre is a leading college and graduate admissions consultant with extensive experience in education and entrepreneurship. His advice has been featured on Forbes.com, U.S. News, CNN Business, the Washington Post, ABC News, Business Insider, and more.

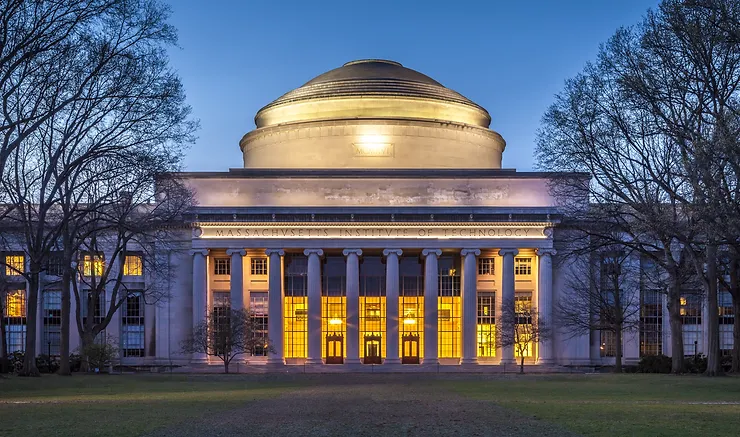

As the Massachusetts Institute of Technology explains on its admissions website, they’ve chosen to eschew the Common App (good for them!) and ask you to write a series of short responses, without the long personal statement.

Here they are.

We know you lead a busy life, full of activities, many of which are required of you. Tell us about something you do simply for the pleasure of it. (100 words or fewer)

As you’re writing your twenty-third essay for college admissions, you may find yourself wondering if this process is not, in fact, an elaborate ruse designed to torture you. Remember that these essays do serve an important purpose: they help colleges get to know you as a student, but also as a person.

That’s the point of this question. The prompt isn’t “tell us something you like to do,” but rather “tell us about something you do simply for the pleasure of it.” See the difference? You may like physics, or football, or community service, but you probably get some form of credit for participating in these endeavors, even if it’s only the chance to list them on their transcripts and activities list. What’s something you do and don’t get credit for? What’s something that doesn’t appear on your transcript or activities list, but that you genuinely love doing?

Examples: listening to This American Life; gardening; collecting stamps; converting your dad’s old Specialized to an electric bicycle; rock climbing; waking up early and making pancakes for your family; scrapbooking; playing pinball…

The possibilities are absolutely endless. Talk about one of your “useless” passions, and make it something quirky—the response has to be original, and show something unique and intriguing about who you are. There aren’t necessarily any bad topics here, but if you choose a highly typical “pleasurable” activity (like eating ice cream and watching Game of Thrones) you better have something truly unexpected to say about it. After all, you’re trying to stand out from the pack.

Resist the temptation to make your pleasurable activity out to be some grand endeavor, since this runs counter to what the question is all about. In other words, don’t say: “Fly fishing is challenging, but through this activity I have learned the virtues of precision and patience.” If you’re being challenged and learning virtues, it doesn’t sound like you’re fishing for pleasure, and ending on a moral like this is just too typical. Tell a compelling story, and let your narrative show what the message is.

Although you may not yet know what you want to major in, which department or program at MIT appeals to you and why? (100 words or fewer)

Do your research for this one. MIT doesn’t have a typical “Why This College” prompt, so this is as close as you get. It’s your chance to explain how your experiences and achievements relate to what MIT can offer. It’s a very short response, so don’t waste any time talking about the lovely urban campus or the “world-class” faculty, etc. Give specific and convincing examples of why a particular department or program at MIT attracts you, and why your background makes the fit make sense.

At MIT, we bring people together to better the lives of others. MIT students work to improve their communities in different ways, from tackling the world’s biggest challenges to being a good friend. Describe one way in which you have contributed to your community, whether in your family, the classroom, your neighborhood, etc. (200-250 words)

As always, these questions are a little hard to answer without sounding like you’re making yourself out to be a hero—and you want to avoid that. So if you’re going to talk about the non-profit you created, be matter-of-fact about your accomplishments. On the other hand, if you’ve never done anything earth-shattering to help humanity (like most people who get into MIT), you probably don’t want to write about filling potholes in your school’s driveway (something they made me do for acting out in French class).

Ideally, you always want to avoid talking about anything that’s already on your activities list, since admissions officers already know about that. If you can write about some way you’ve helped your community that you’ve never gotten credit for, and if it’s a good story, go for it. (Maybe you babysat your neighbor’s kids for a month while their mom was in the hospital or something.) If you have to talk about something that already appears on your activities list, make sure you’re going beyond a simple description of the project. Tell us a story about it.

Do not talk about anything that was required of you. You may have done a whole lot of good on a school service trip, or fulfilling your community service requirement, and those activities are meaningful in ways that are far more important than the college admissions process. But on your college applications, required activities say very little about who you are. Make sure that, whatever you choose to talk about, it was your choice, and not a requirement.

Describe the world you come from; for example, your family, clubs, school, community, city, or town. How has that world shaped your dreams and aspirations? (200-250 words)

This is a great question. Think about what is unique about your world, and remember that “world,” like “community,” can mean just about anything.

As always, the goal is to stand out and be remembered, so think long and hard about what is particular and personal about where you come from, where you spend your time, and where you matter. Even if you’re pretty typical as a college applicant (let’s say you’re a white kid from the suburbs of Boston who attends a mid-sized private school), I promise there is something intriguing about your world—or at least something interesting to be said about it. Do not try to make yourself out to be exotic, regardless of who you are—this must be authentic. Maybe “your world” is really an online community of programmers. Maybe you’re a scenester in Louisville (or whatever the kids in Louisville are calling themselves these days). Maybe your community is your synagogue, where you play an important role. I don’t know, this is a deeply personal question. But remember that “world” can have a very broad definition—“your world” is for you to define. I love brainstorming questions like this with students. Talk it out with me, or with your friends, family, neighbors, etc.

Tell us about the most significant challenge you’ve faced or something important that didn’t go according to plan. How did you manage the situation? (200-250 words)

First off, let me say that I’ve helped students write about some pretty heavy challenges, and I know from experience that it can be tough to talk about such things. Remember that you are under no obligation to talk about anything you don’t feel comfortable sharing. I object to the way the question is framed: “the most significant challenge you’ve faced.” You don’t have to tell MIT about your “most significant challenge” if you don’t want to.

If you’ve read my blog in the past, you know that I’m not a fan of questions like this. Even for students who have “easy” answers to questions like this—students who’ve encountered real hardships—these experiences can be difficult to present effectively. Basic guidelines: don’t complain, don’t blame, don’t make yourself out to be simply a victim (even if you were/are a victim). The most compelling essays about challenges demonstrate a capacity for perspective and introspection. You can write with emotion, but make sure you are also writing with perspective.

If you haven’t faced a significant challenge, now is your chance to demonstrate self-awareness. Do not exaggerate your hardships. Do not present the fact that you broke your leg during a hockey game as an example of true adversity. If this kind of thing is the worst that has ever happened to you, count yourself lucky, and keep in mind that your readers may well have experienced far worse, and have certainly read about far worse. If you have nothing “impressive” to say, that’s fine. Just make it clear that you know you’re writing about something that has personal significance, but isn’t a really big deal, all things considered. Mundane stories can say a lot about a person. You just have to make it apparent that you’re aware that your story is mundane. Humor is one way to accomplish this.

Regardless of what you choose to talk about, make sure you demonstrate how you responded to the difficulty. Avoid ending on a moral—the story should make clear what the message is. Show it through your narrative. You shouldn’t have to come out and say it.

There is also one final, open-ended additional information text box, where you can tell us anything else you think we really ought to know.

This is a little bit like the section on the Common App that asks for additional information. Depending on your situation, you may want to use this to explain or highlight something about your high school career that does not already appear on your application.

As always, Ivy League admission consultants are here to help. Don’t hesitate to reach out.